Greetings

Welcome to my little web space on music theory. I’ve built it partly to demonstrate some web design – and partly to regurgitate information so I can put it in an orderly fashion outside my head. The content here is aimed at those who have some musical knowledge (e.g. they know all the Major scales) but not much more than that (e.g. they don’t know about borrowed chords from parallel scales). You can find such information (and more) elsewhere – but the internet is an ocean and swimming through things takes time. On this website, I summarise what I wish someone had shown me when I began digging deeper into theory. I start off with scales (including modes) in a section called Basic Music Theory. I then describe Diatonic Chords (with chord progressions and chord formulas) before introducing Non-Diatonic Chords. The last two sections (Song Writing and Extras) are much more piecemeal and might be added to later.

That’s all you need to know, but if you want some context around why I started making this site, you can read below.

Like many others, I learned classical piano when young. That ended abruptly in adolescence and then I played no music until age 30, when I picked up my dad’s guitar. The approach to music could not have been more different. Thanks to the piano, I could fingerpick TAB, but what on Earth were those ‘chord names’ written above that TAB – like G7 or Gm, or heaven forbid, Gm7? After some years, I tried a guitar teacher, who said I was proficient but my weakness was theory – so off I went, to binge on Signals Music Studio at YouTube. I’m plugging Jake Lizzio’s channel 100%. (I also subscribe to his Patreon as a way of saying thanks.)

Aside from making music, I like to make things in general, and for work, I also made eLearning content with programs like Captivate. On the side, I started to make charts for this website with a view to turning them into interactive resources. Then along the way popped up a guy on Reddit, saying that he’d just finished making an interactive website with a similar purpose. I encourage you to check out his site at chordcolors.com. I liaised with him soon after (hi Ross!) and shared some of my ideas with him – since I killed my project after seeing how far he was with his. I hope things work out for him.

On his site, you can swap between different chords that have the same function, and you can see where to play those on either a keyboard or guitar. His website also lets you try out and save different chord progressions, and it has a nice Circle of Fifths tool.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t obviously explain all the features of his website (or not at the time of writing), such as for the Circle of Fifths tool, so be sure to read his Help menu in detail. Also, he doesn’t explain why you would use his tools; it’s presumed that you have an understanding of music theory – and that’s where my ‘information dump’ might come in handy to you.

Greetings

Welcome to my little web space on music theory. I’ve built it partly to demonstrate some web design – and partly to regurgitate information so I can put it in an orderly fashion outside my head. The content here is aimed at those who have some musical knowledge (e.g. they know all the Major scales) but not much more than that (e.g. they don’t know about borrowed chords from parallel scales). You can find such information (and more) elsewhere – but the internet is an ocean and swimming through things takes time. On this website, I summarise what I wish someone had shown me when I began digging deeper into theory. I start off with scales (including modes) in a section called Basic Music Theory. I then describe Diatonic Chords (with chord progressions and chord formulas) before introducing Non-Diatonic Chords. The last two sections (Song Writing and Extras) are much more piecemeal and might be added to later.

That’s all you need to know, but if you want some context around why I started making this site, you can read below.

Like many others, I learned classical piano when young. That ended abruptly in adolescence and then I played no music until age 30, when I picked up my dad’s guitar. The approach to music could not have been more different. Thanks to the piano, I could fingerpick TAB, but what on Earth were those ‘chord names’ written above that TAB – like G7 or Gm, or heaven forbid, Gm7? After some years, I tried a guitar teacher, who said I was proficient but my weakness was theory – so off I went, to binge on Signals Music Studio at YouTube. I’m plugging Jake Lizzio’s channel 100%. (I also subscribe to his Patreon as a way of saying thanks.)

Aside from making music, I like to make things in general, and for work, I also made eLearning content with programs like Captivate. On the side, I started to make charts for this website with a view to turning them into interactive resources. Then along the way popped up a guy on Reddit, saying that he’d just finished making an interactive website with a similar purpose. I encourage you to check out his site at chordcolors.com. I liaised with him soon after (hi Ross!) and shared some of my ideas with him – since I killed my project after seeing how far he was with his. I hope things work out for him.

On his site, you can swap between different chords that have the same function, and you can see where to play those on either a keyboard or guitar. His website also lets you try out and save different chord progressions, and it has a nice Circle of Fifths tool.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t obviously explain all the features of his website (or not at the time of writing), such as for the Circle of Fifths tool, so be sure to read his Help menu in detail. Also, he doesn’t explain why you would use his tools; it’s presumed that you have an understanding of music theory – and that’s where my ‘information dump’ might come in handy to you.

Basic Music Theory

OK, this is where things are going to get pretty darn dry, pretty darn quickly. This conversational tone you read now, well that’s going, and I’ll become cyborg-like for expediency.

Here we go….

A chord is a collection of notes played at the same time. A group of 3 notes is known as a triad. If a chord has more than 3 notes, it is known as an extended chord, sometimes built over multiple octaves. Extended chords are favoured by jazz musicians. Triad chords are more versatile (a greater variety of other notes can be played on top of them without clashing). A triad can form the basis (the first 3 notes) of different extended chords.

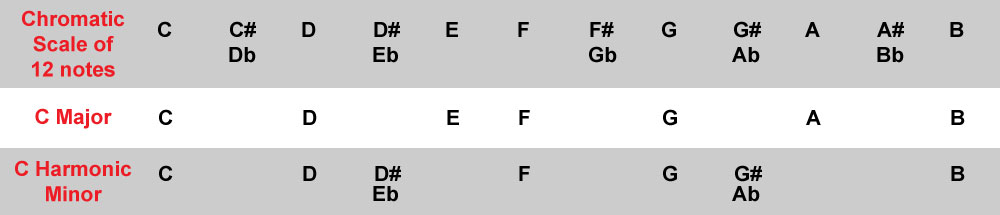

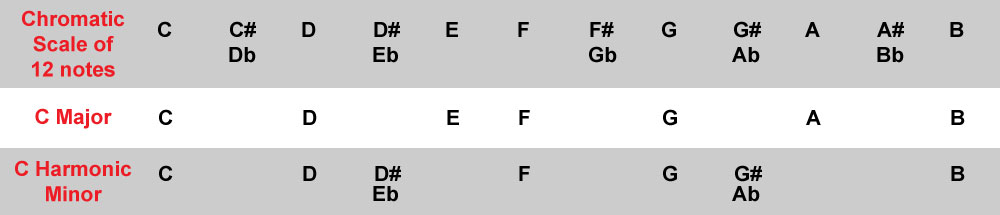

A scale is a collection of notes played in succession with a pre-defined spacing pattern between each note. If you were to play every note within one octave on the piano, there would be 12 notes. That is known as the Chromatic Scale. However, most scales have only 7 unique notes so their spacing pattern dictates which chromatic notes will be omitted. The image below shows the Chromatic, Major and Harmonic Minor scales in the key of C. These are known as pure scales because the spacing patterns between each note are unique.

If two notes are side-by-side, we say that they are a semitone (S) apart. If there is a missing note between them (like between C and D), we say that they are a whole tone (T) apart. Based on this, the spacing pattern for any Major scale is TTSTTTS. The spacing pattern of a Harmonic Minor scale is TSTTS(T.5)S (where T.5 is like saying one and a half. I don’t know how else to say it!)

The spacing of three different pure scales in the key of C:

Each pure scale has its own set of modal scales. The difference between a pure scale and a modal scale is that pure scales have unique spacing patterns, whereas a modal scale is just a pure scale that starts on a different position within the scale. It is not the spacing that’s different between modal scales but the order of that spacing. Look at the example above where Major’s spacing is TTSTTTS and Harmonic Minor’s is TSTTS(T.5)S. If I start on the second position (note D) instead of the first position (note C), I would have a spacing pattern of TSTTTST. At first glance, you may think that is a completely different scale to Major, and it is but only kind of, because it still uses the same collection of notes as C Major. Because modal scales all use the same notes as the pure scale that they are from (just starting and ending at different points), they are known as relative keys (one big happy family). On the other hand, the collection of notes between different pure scales will never be the same.

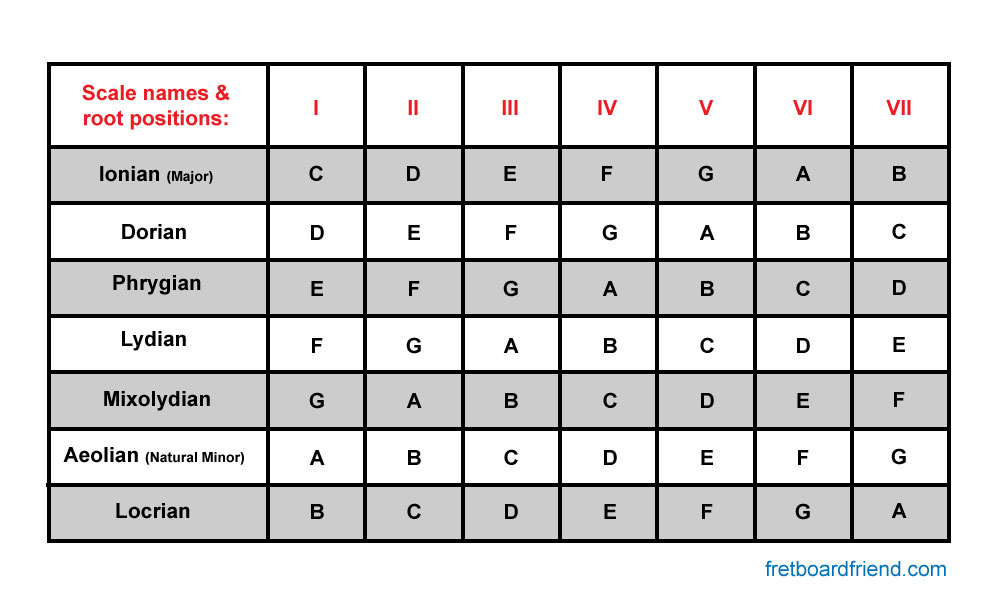

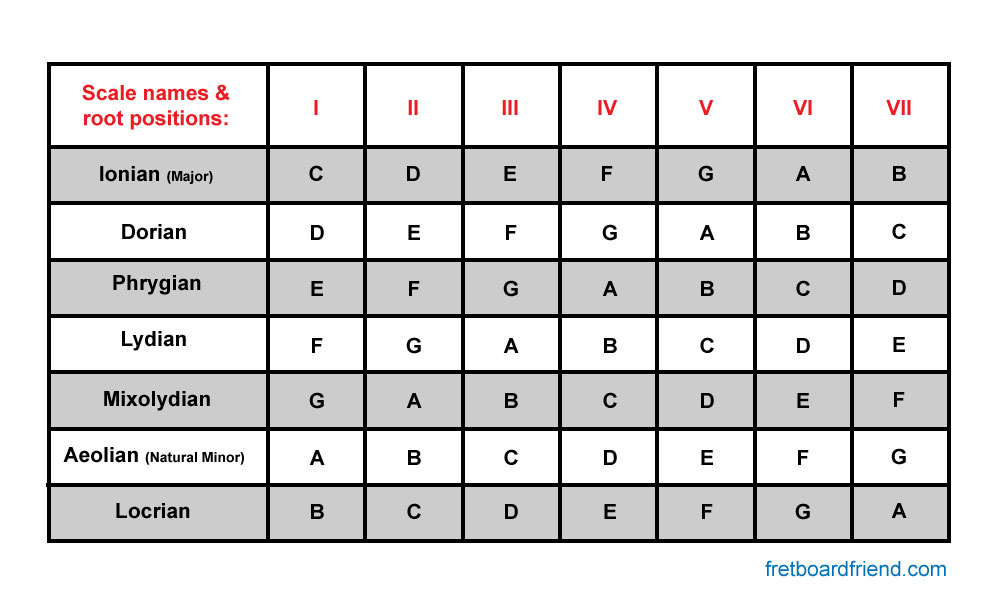

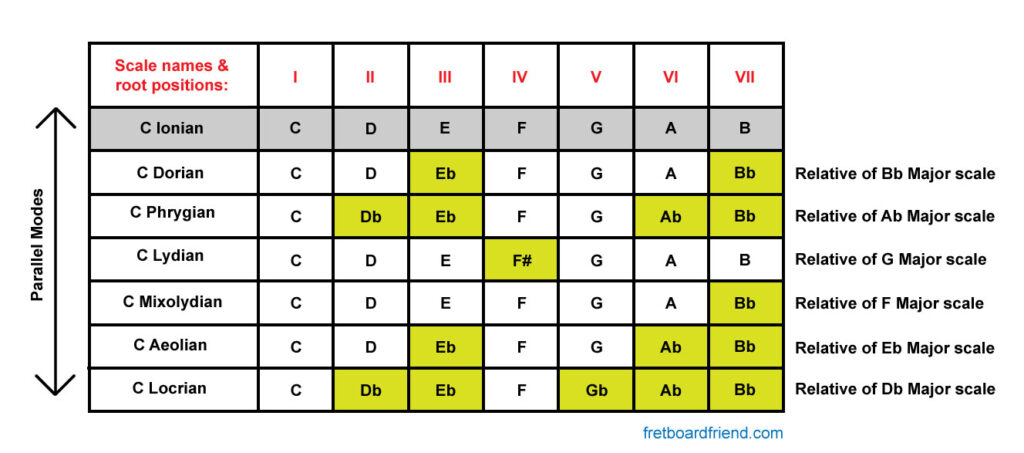

The table below shows all the relative modal scales connected to C Major. Note that the term ‘Ionian’ is synonymous with ‘Major’. Also note that the Aeolian scale is sometimes called the Natural Minor (or just Minor) scale. However, because there are other minor scales (such as Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor), I prefer to write Aeolian to avoid confusion. You can see from the table that A is the 6th note in the C Ionian scale, but conversely, C is the 3rd note within the A Aeolian scale. Order matters when it comes to song progressions, which I’ll describe later.

The happiest-sounding of the Major modes is Ionian (Major itself). The most melancholic is Aeolian. Each mode has its own flavour, with Locrian being the oddest one of the lot. Dorian and Mixolydian are the ones I’d focus on learning after Major and Aeolian.

You might hear people refer to the general sound of a key as ‘major’ or ‘minor’. They may not necessarily be referring to Ionian and Aeolian modes per se, but the tonic chord of the key. (The tonic note is in position I. It is the sound that makes the song feel resolved.) I’ll get into chord types later, but for now, just know that the tonic chords for Dorian, Phrygian and Aeolian are minor, so those keys tend to sound reflective and not so upbeat. The rest are Major, except for Locrian, which is doing its own thing.

It’s worth noting here that there are some scales with fewer than 7 notes (namely Pentatonic Major, Pentatonic Minor and Blues). You can think of those as condensed scales. They don’t really fit when it comes to building diatonic chords but they are useful in their own right, for targeting notes while playing lead (melodic lines over a chord progression). Likewise, there can be musical frameworks that have more than 7 notes in a scale. After all, notes are arbitrarily imposed on a continuum of sound frequencies so we can cut that frequency into as many pieces as we like. For the purposes of this website, we are only looking at scales with 7 distinct notes, and of those, only the modes of Major and 2 modes of Harmonic Minor. If you’re interested in other scales, like Bepop and Melodic Minor, look them up elsewhere.

The relative modes of C Major. (Same collection of notes, same key signature, different starting note):

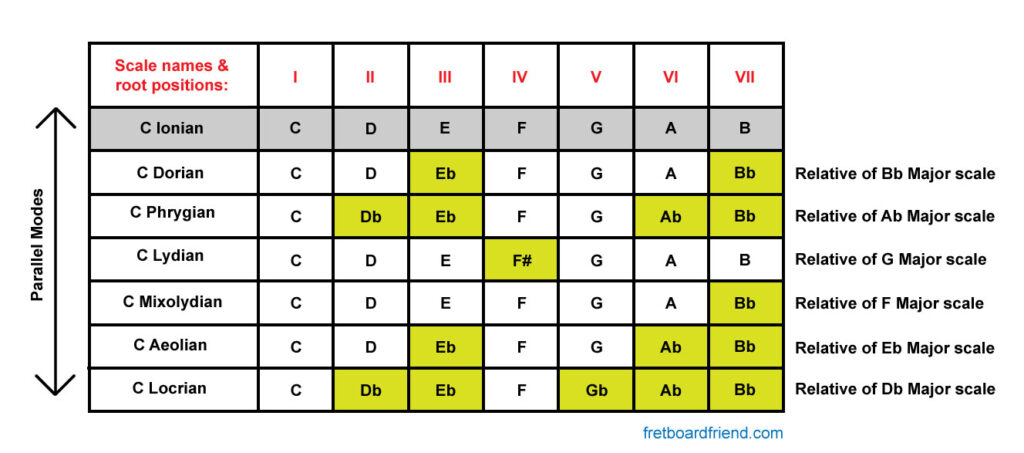

A key is defined by both the scale type and the tonic note that begins the scale. The table above shows the relative keys of C Major (with D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Mixolydian etc.) However, we can also consider parallel keys (not relative keys) as per the table below. It is important to distinguish between relative and parallel keys. You can swap between them (such as between a verse and a chorus) or, if careful, borrow chords from them while staying in one main key.

Playing parallel keys, as per the table below, will give you a better appreciation of the different flavour of each mode (instead of playing relative keys, like in the table above).

The parallel modes of C Major. (Same starting note but different starting point on the spacing pattern of the Major scale. This means that parallel modes do not share a time signature):

A key signature will tell you if any notes are sharp (#) or flat (b) within the scale. Sharp means ‘up by a semitone’ and flat means ‘down by a semitone’, so D# is the same as Eb because they both refer to the same note between D and E.

There is a difference between the words ‘sharp’ and ‘sharped’, and ‘flat’ and ‘flatted’. Sharp and flat notes are distinct points on the sound spectrum. D# is one particular sound, just as D (natural) and Db are. However, D ‘sharped’ is when the note has been raised by a semitone beyond what it normally would be for the key. It is more usually applied to the a position of a note, e.g. the second position is ‘sharped’. In that case, the second position could be any note, such as D, D# or E…. D sharped would be D#. D# sharped would be E. E sharped would be F. Ditto in reverse for ‘flatted’. Hope that makes sense.

And while we’re talking about specific notes occupying specific points on the sound spectrum, you should know that there is a rift in musical measurements, just as there is between Celsius and Fahrenheit for temperature, or inches and centimetres for distance. Basically, ‘middle C’ is not the same sound across all instruments, just as 0 degrees Celsius is not the same temperature as 0 degrees Fahrenheit. The piano and guitar are both considered ‘concert pitch’ instruments so they follow the same naming of sound frequencies. However, most horned and certain other stringed instruments assign different sound frequencies. There is even a discrepancy between the alto sax and tenor sax – so it can seem as if each instrument is playing in a different key when in fact, they are playing in the same key but the scale name has shifted to suit the different (and rather arbitrary) demarcation of frequencies. Why can’t we all use kelvins, metrics and concert pitch measurements?!

But I digress. There is nothing inherently special about a key signature with sharps or flats. I suspect those sound frequency labels (#/b) became vernacular on account of the piano, whose white notes all correspond to just one Major scale (C). The black notes were named sharp/flat relative to that scale. The guitar fretboard is much more egalitarian in its layout. Sharps and flats look no different to any other note on the guitar.

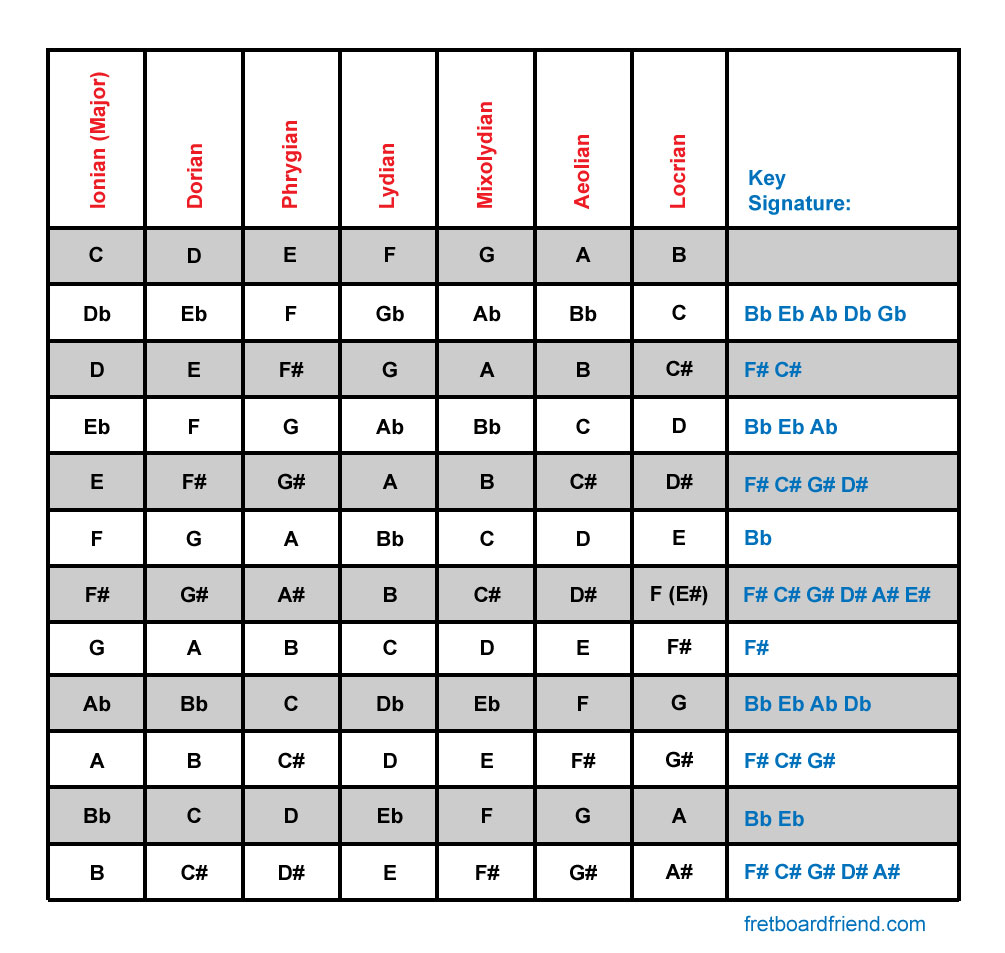

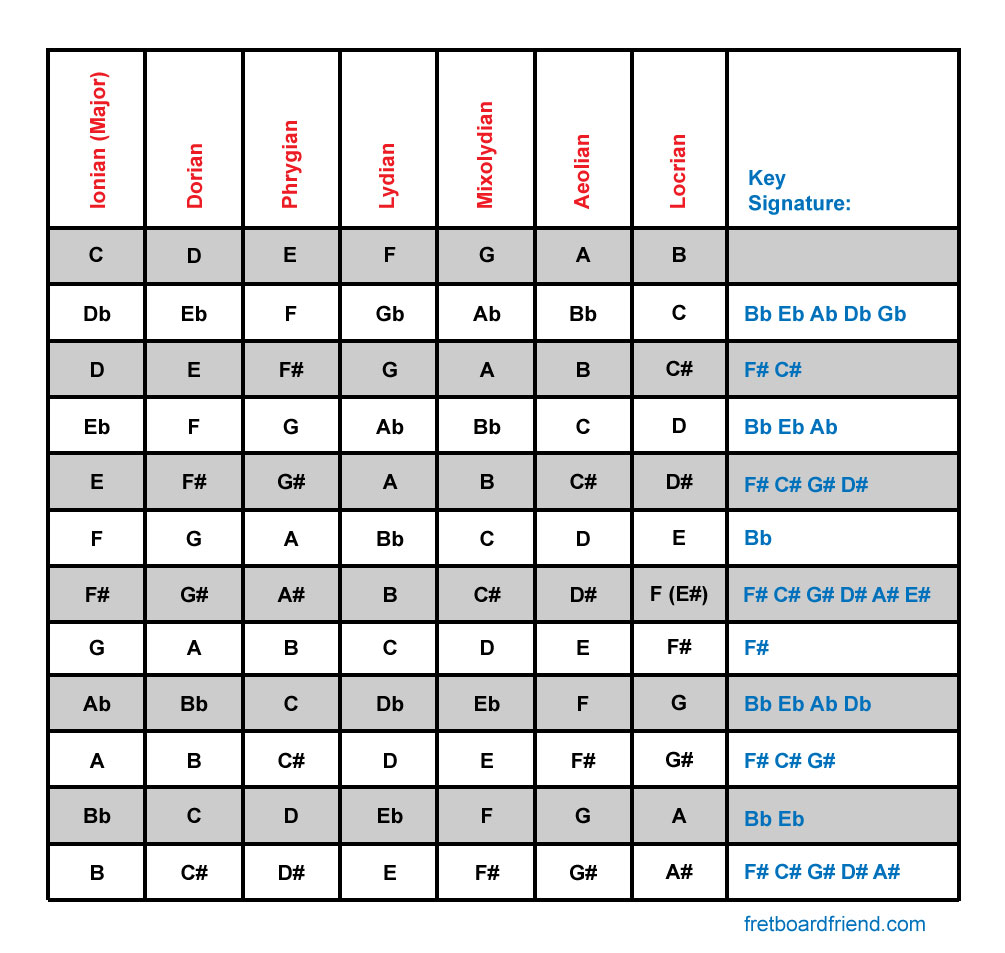

The table below shows the key signatures for every Major scale and you can deduce from that the corresponding key signatures for each relative and parallel scale. This is a handy table to have in your back pocket, when first hearing a song and trying to work out its key based on its sharps and flats.

The key signatures of all relative and parallel modes of Major:

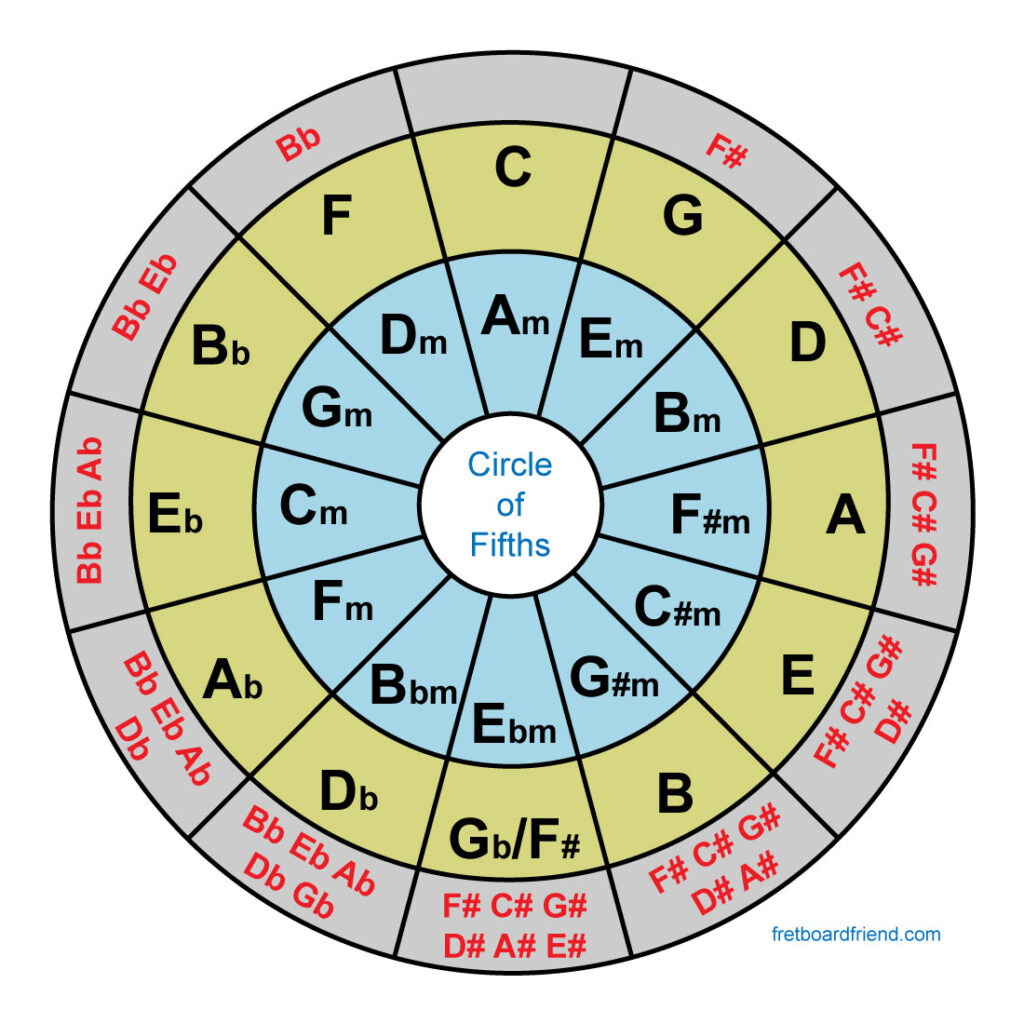

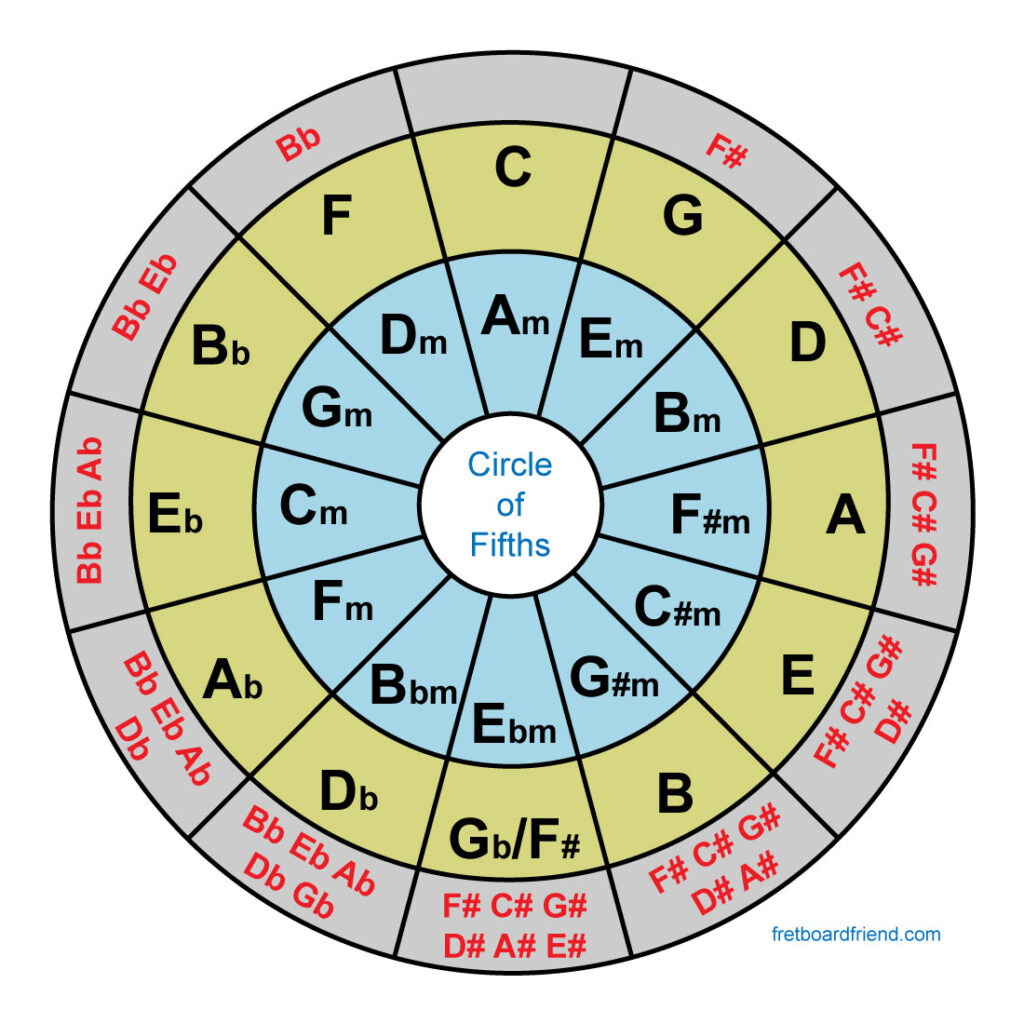

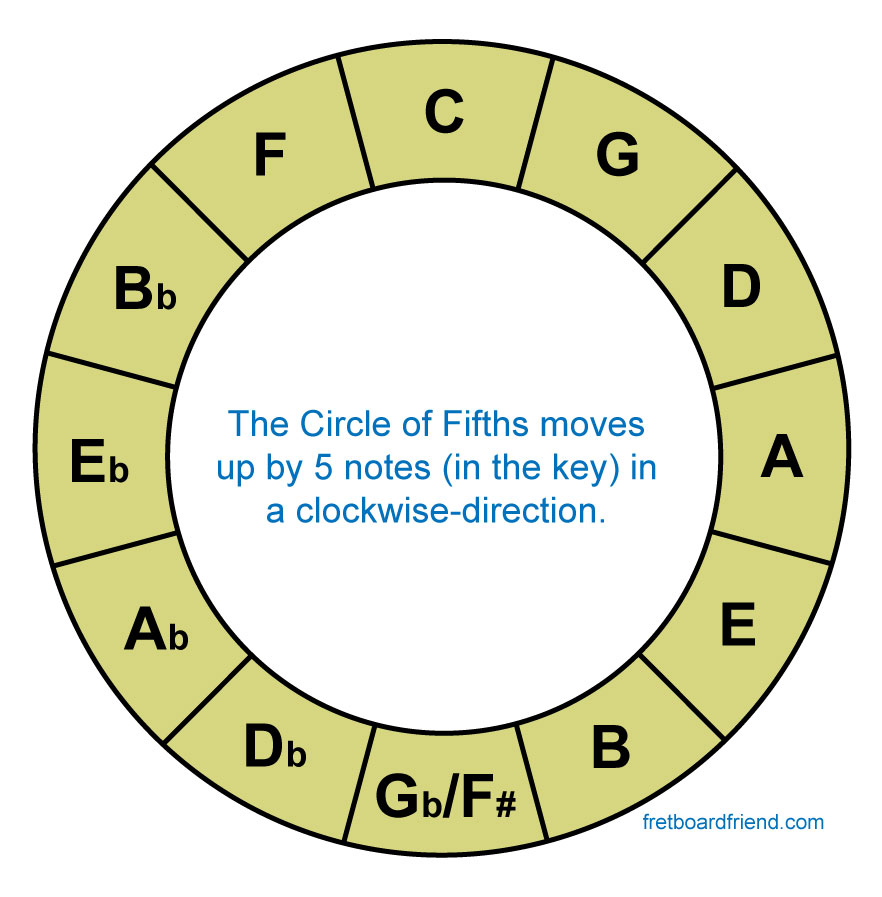

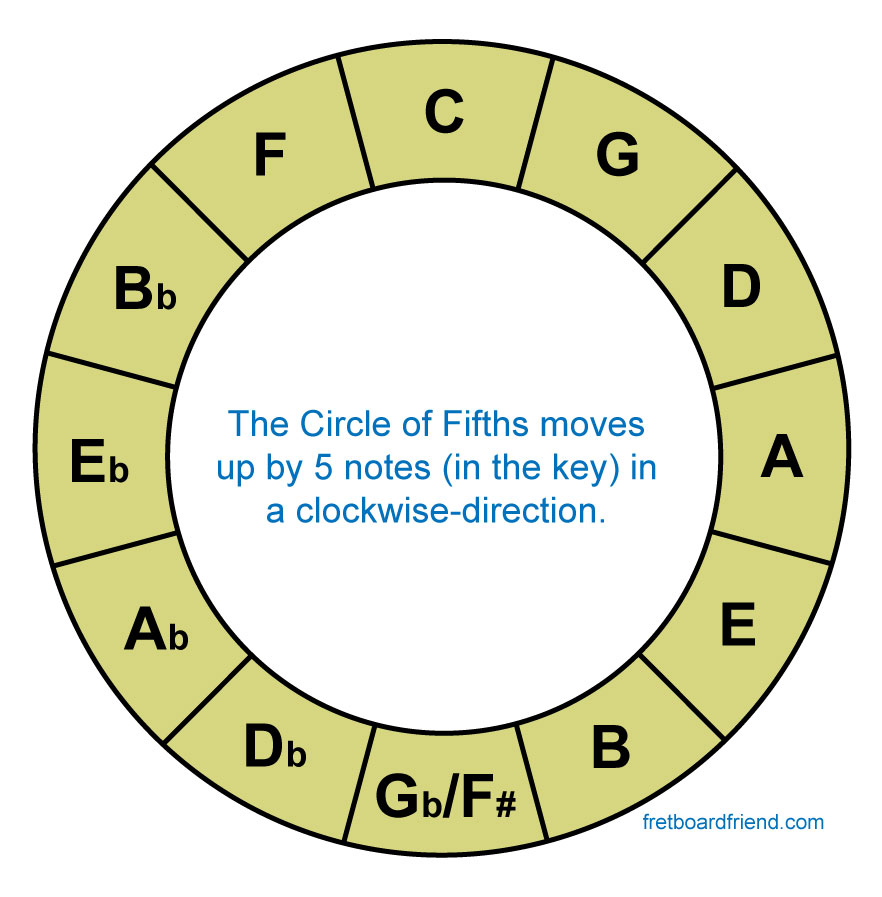

The table above is quite dense. A faster way of glancing at a key signature is to use the Circle of Fifths diagram (see below) with overlays. You can print the image below and place a clear plastic overlay on top, or look up an online interactive Circle of Fifths tool.

The yellow ring in the diagram below shows the Ionian keys and the blue inner ring shows their corresponding Aeolian keys. (Aeolian keys are the second-most popular after Ionian/Major keys). The grey outer ring shows the shared key signature for each pair of relative keys. For example, C Ionian and A Aeolian are relative keys and they have no sharps or flats.

The circle of fifths:

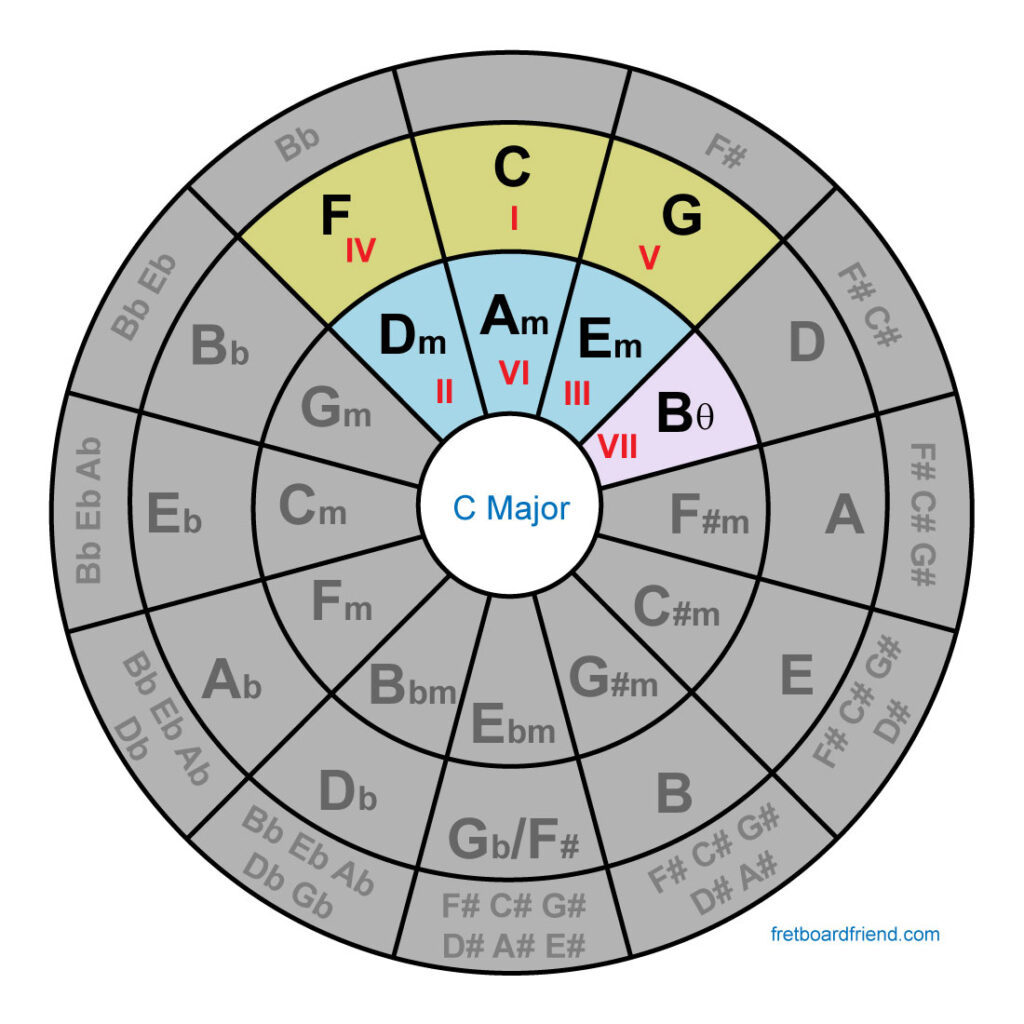

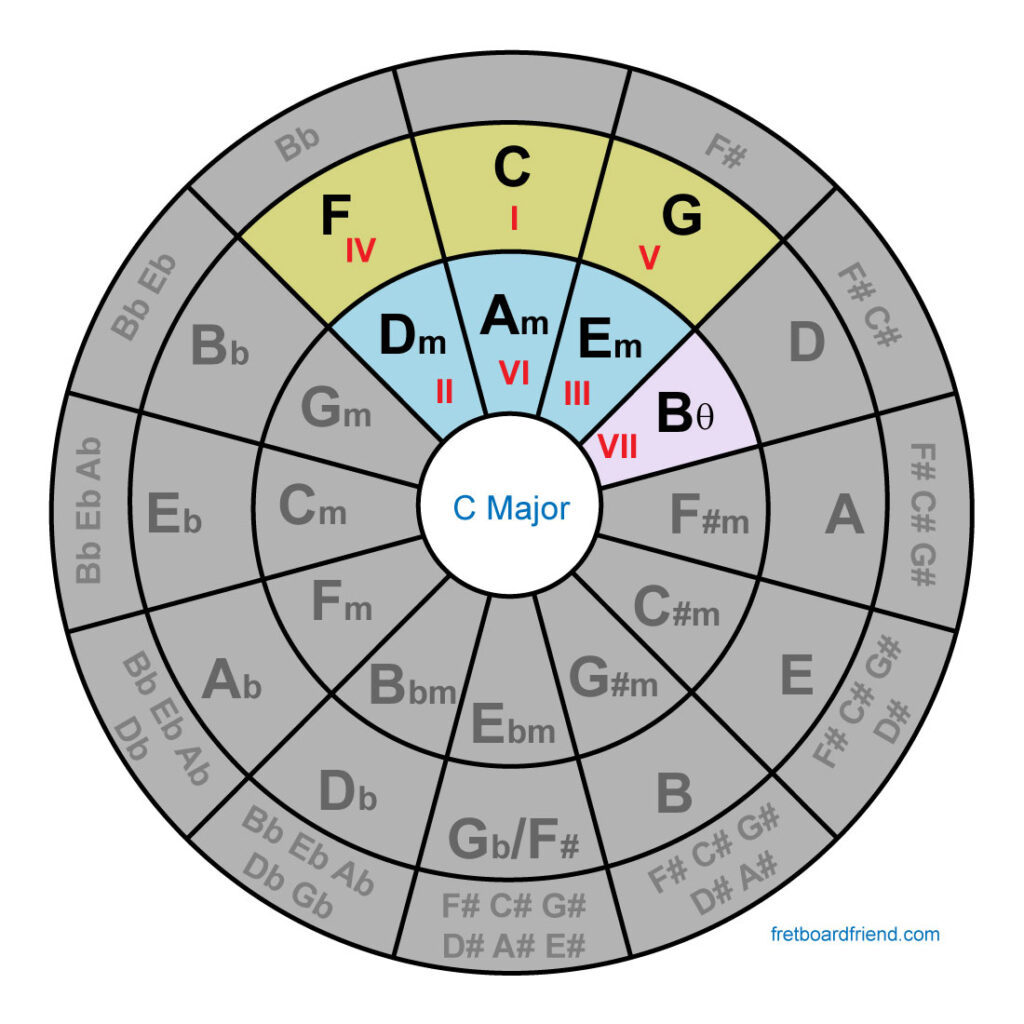

Below is the Circle of Fifths below with an overlay applied for the key of C Major. That key’s diatonic chord positions are labelled in red. Diatonic chords will be explained in the next section. The position of those chord types (noted in red) can be spun onto any point in the wheel so you can quickly see what diatonic chords are in any Ionian key. (Various overlays are one of the interactive resources I was going to develop. I may yet add them to the Extras section one day.)

The circle of fifths with a overlay of Ionian diatonic chords:

Now you should have a reasonable idea of scales in the Major world – but there are many other ‘pure’ scales aside from Major. Have you heard of the Hungarian Minor scale, the Neapolitan scale, the Prometheus scale or Hirajoshi scale? …Me neither. But if you like a slightly exotic sound (along the lines of Santana, some flamenco or Middle Eastern music, and even some songs by Tool) then I recommend the Harmonic Minor scale as a non-Western key to dip your toes into. Just like the Major scale, the Harmonic Minor scale has 7 related modal scales. Other than the first mode (Harmonic Minor itself), the fifth mode is interesting – i.e. the Phrygian Dominant scale. This is distinct from the Phrygian scale, which is the 3rd mode of the Major scale. The spacings between the Phrygian and Phrygian Dominant scales aren’t very different, just as the spacing between the Aeolian (Natural Minor) and Harmonic Minor scales is not too different. That means you can use common (shared) chords between these keys to pivot between them. (Changing keys within a song is known as modulation.) Changing keys means changing chords, a bit like spinning the overlay on the Circle of Fifths. I’m jumping the gun a bit, but keep that Circle of Fifths in mind as you move onto the next section of Diatonic Chords.

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Basic Music Theory

OK, this is where things are going to get pretty darn dry, pretty darn quickly. This conversational tone you read now, well that’s going, and I’ll become cyborg-like for expediency.

Here we go….

A chord is a collection of notes played at the same time. A group of 3 notes is known as a triad. If a chord has more than 3 notes, it is known as an extended chord, sometimes built over multiple octaves. Extended chords are favoured by jazz musicians. Triad chords are more versatile (a greater variety of other notes can be played on top of them without clashing). A triad can form the basis (the first 3 notes) of different extended chords.

A scale is a collection of notes played in succession with a pre-defined spacing pattern between each note. If you were to play every note within one octave on the piano, there would be 12 notes. That is known as the Chromatic Scale. However, most scales have only 7 unique notes so their spacing pattern dictates which chromatic notes will be omitted. The image below shows the Chromatic, Major and Harmonic Minor scales in the key of C. These are known as pure scales because the spacing patterns between each note are unique.

If two notes are side-by-side, we say that they are a semitone (S) apart. If there is a missing note between them (like between C and D), we say that they are a whole tone (T) apart. Based on this, the spacing pattern for any Major scale is TTSTTTS. The spacing pattern of a Harmonic Minor scale is TSTTS(T.5)S (where T.5 is like saying one and a half. I don’t know how else to say it!)

The spacing of three different pure scales in the key of C:

Each pure scale has its own set of modal scales. The difference between a pure scale and a modal scale is that pure scales have unique spacing patterns, whereas a modal scale is just a pure scale that starts on a different position within the scale. It is not the spacing that’s different between modal scales but the order of that spacing. Look at the example above where Major’s spacing is TTSTTTS and Harmonic Minor’s is TSTTS(T.5)S. If I start on the second position (note D) instead of the first position (note C), I would have a spacing pattern of TSTTTST. At first glance, you may think that is a completely different scale to Major, and it is but only kind of, because it still uses the same collection of notes as C Major. Because modal scales all use the same notes as the pure scale that they are from (just starting and ending at different points), they are known as relative keys (one big happy family). On the other hand, the collection of notes between different pure scales will never be the same.

The table below shows all the relative modal scales connected to C Major. Note that the term ‘Ionian’ is synonymous with ‘Major’. Also note that the Aeolian scale is sometimes called the Natural Minor (or just Minor) scale. However, because there are other minor scales (such as Harmonic Minor and Melodic Minor), I prefer to write Aeolian to avoid confusion. You can see from the table that A is the 6th note in the C Ionian scale, but conversely, C is the 3rd note within the A Aeolian scale. Order matters when it comes to song progressions, which I’ll describe later.

The happiest-sounding of the Major modes is Ionian (Major itself). The most melancholic is Aeolian. Each mode has its own flavour, with Locrian being the oddest one of the lot. Dorian and Mixolydian are the ones I’d focus on learning after Major and Aeolian.

You might hear people refer to the general sound of a key as ‘major’ or ‘minor’. They may not necessarily be referring to Ionian and Aeolian modes per se, but the tonic chord of the key. (The tonic note is in position I. It is the sound that makes the song feel resolved.) I’ll get into chord types later, but for now, just know that the tonic chords for Dorian, Phrygian and Aeolian are minor, so those keys tend to sound reflective and not so upbeat. The rest are Major, except for Locrian, which is doing its own thing.

It’s worth noting here that there are some scales with fewer than 7 notes (namely Pentatonic Major, Pentatonic Minor and Blues). You can think of those as condensed scales. They don’t really fit when it comes to building diatonic chords but they are useful in their own right, for targeting notes while playing lead (melodic lines over a chord progression). Likewise, there can be musical frameworks that have more than 7 notes in a scale. After all, notes are arbitrarily imposed on a continuum of sound frequencies so we can cut that frequency into as many pieces as we like. For the purposes of this website, we are only looking at scales with 7 distinct notes, and of those, only the modes of Major and 2 modes of Harmonic Minor. If you’re interested in other scales, like Bepop and Melodic Minor, look them up elsewhere.

The relative modes of C Major. (Same collection of notes, same key signature, different starting note):

A key is defined by both the scale type and the tonic note that begins the scale. The table above shows the relative keys of C Major (with D Dorian, E Phrygian, F Mixolydian etc.) However, we can also consider parallel keys (not relative keys) as per the table below. It is important to distinguish between relative and parallel keys. You can swap between them (such as between a verse and a chorus) or, if careful, borrow chords from them while staying in one main key.

Playing parallel keys, as per the table below, will give you a better appreciation of the different flavour of each mode (instead of playing relative keys, like in the table above).

The parallel modes of C Major. (Same starting note but different starting point on the spacing pattern of the Major scale. This means that parallel modes do not share a time signature):

A key signature will tell you if any notes are sharp (#) or flat (b) within the scale. Sharp means ‘up by a semitone’ and flat means ‘down by a semitone’, so D# is the same as Eb because they both refer to the same note between D and E.

There is a difference between the words ‘sharp’ and ‘sharped’, and ‘flat’ and ‘flatted’. Sharp and flat notes are distinct points on the sound spectrum. D# is one particular sound, just as D (natural) and Db are. However, D ‘sharped’ is when the note has been raised by a semitone beyond what it normally would be for the key. It is more usually applied to the a position of a note, e.g. the second position is ‘sharped’. In that case, the second position could be any note, such as D, D# or E…. D sharped would be D#. D# sharped would be E. E sharped would be F. Ditto in reverse for ‘flatted’. Hope that makes sense.

And while we’re talking about specific notes occupying specific points on the sound spectrum, you should know that there is a rift in musical measurements, just as there is between Celsius and Fahrenheit for temperature, or inches and centimetres for distance. Basically, ‘middle C’ is not the same sound across all instruments, just as 0 degrees Celsius is not the same temperature as 0 degrees Fahrenheit. The piano and guitar are both considered ‘concert pitch’ instruments so they follow the same naming of sound frequencies. However, most horned and certain other stringed instruments assign different sound frequencies. There is even a discrepancy between the alto sax and tenor sax – so it can seem as if each instrument is playing in a different key when in fact, they are playing in the same key but the scale name has shifted to suit the different (and rather arbitrary) demarcation of frequencies. Why can’t we all use kelvins, metrics and concert pitch measurements?!

But I digress. There is nothing inherently special about a key signature with sharps or flats. I suspect those sound frequency labels (#/b) became vernacular on account of the piano, whose white notes all correspond to just one Major scale (C). The black notes were named sharp/flat relative to that scale. The guitar fretboard is much more egalitarian in its layout. Sharps and flats look no different to any other note on the guitar.

The table below shows the key signatures for every Major scale and you can deduce from that the corresponding key signatures for each relative and parallel scale. This is a handy table to have in your back pocket, when first hearing a song and trying to work out its key based on its sharps and flats.

The key signatures of all relative and parallel modes of Major:

The table above is quite dense. A faster way of glancing at a key signature is to use the Circle of Fifths diagram (see below) with overlays. You can print the image below and place a clear plastic overlay on top, or look up an online interactive Circle of Fifths tool.

The yellow ring in the diagram below shows the Ionian keys and the blue inner ring shows their corresponding Aeolian keys. (Aeolian keys are the second-most popular after Ionian/Major keys). The grey outer ring shows the shared key signature for each pair of relative keys. For example, C Ionian and A Aeolian are relative keys and they have no sharps or flats.

The circle of fifths:

Below is the Circle of Fifths below with an overlay applied for the key of C Major. That key’s diatonic chord positions are labelled in red. Diatonic chords will be explained in the next section. The position of those chord types (noted in red) can be spun onto any point in the wheel so you can quickly see what diatonic chords are in any Ionian key. (Various overlays are one of the interactive resources I was going to develop. I may yet add them to the Extras section one day.)

The circle of fifths with a overlay of Ionian diatonic chords:

Now you should have a reasonable idea of scales in the Major world – but there are many other ‘pure’ scales aside from Major. Have you heard of the Hungarian Minor scale, the Neapolitan scale, the Prometheus scale or Hirajoshi scale? …Me neither. But if you like a slightly exotic sound (along the lines of Santana, some flamenco or Middle Eastern music, and even some songs by Tool) then I recommend the Harmonic Minor scale as a non-Western key to dip your toes into. Just like the Major scale, the Harmonic Minor scale has 7 related modal scales. Other than the first mode (Harmonic Minor itself), the fifth mode is interesting – i.e. the Phrygian Dominant scale. This is distinct from the Phrygian scale, which is the 3rd mode of the Major scale. The spacings between the Phrygian and Phrygian Dominant scales aren’t very different, just as the spacing between the Aeolian (Natural Minor) and Harmonic Minor scales is not too different. That means you can use common (shared) chords between these keys to pivot between them. (Changing keys within a song is known as modulation.) Changing keys means changing chords, a bit like spinning the overlay on the Circle of Fifths. I’m jumping the gun a bit, but keep that Circle of Fifths in mind as you move onto the next section of Diatonic Chords.

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Diatonic Chords

The last section described different scale types (pure, relative and parallel). This section describes different chord types in different positions within a scale/key. It also introduces the idea of chord progressions, chord formulas and chord-group functions. Indeed, things get extra dry below but you’ve got to know this stuff if you want to intentionally break rules later.

Every key has a set of diatonic chords for each root note (each position) within the scale. Diatonic means ‘within the key’ so nothing will sound out of tune. If everyone sticks to playing diatonic chords together, things can’t go too wrong. Just choose a key and stick to that set of chord types. Better yet, agree on a chord progression (the order that the chords are played in) and bingo, you have a song.

I won’t explain how diatonic chords are arrived at because your eyes may already be glazing over and I don’t want to lose you. Check out Jake Lizzio’s videos on YouTube if you want to know more. Otherwise just take it for granted that each key has a set of diatonic chord types for each position within the scale.

Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV etc.) show the position of each chord within the scale. Song progressions are written with these Roman numerals. For example, we could write a progression as I-IV-V-I. If we played that in the key of C Major (C Ionian), those chords would be C Major chord, then F Major chord, G Dominant chord (or G Major triad), back to C Major chord.

Note: If a chord is a Major chord, we don’t usually bother specifying that (as I did above). We would just write C-F-G7-C, where ‘7’ (not ‘maj7’ or ‘min7’ stands for ‘dominant 7’). If you’re not familiar with chord notations, check out this link. Note that some people distinguish between a Major and Minor chord in the chord progression by using capital Roman letters for Major (like I) and lower case Roman letters for Minor (i). I’m just going to use all caps and add the small ‘m’ to signify a Minor chord – so II = a Major chord but IIm = a Minor chord.

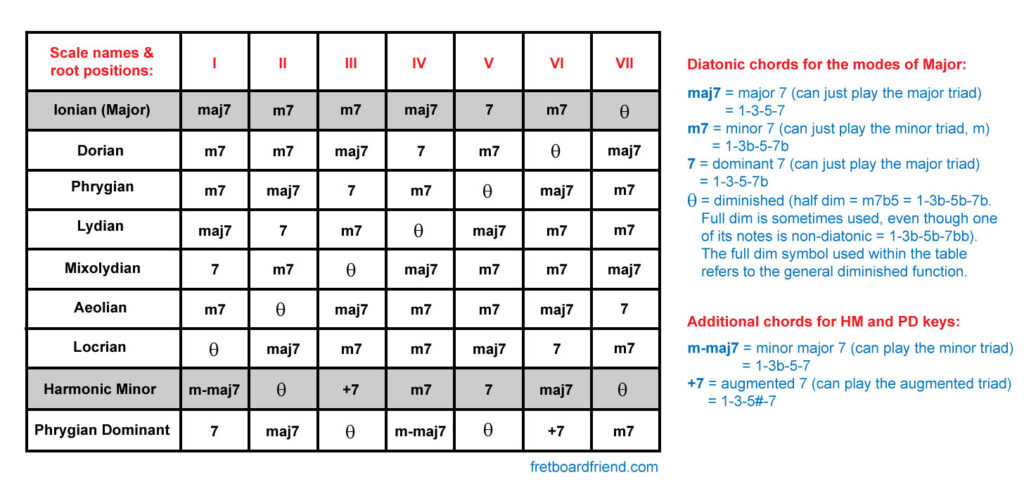

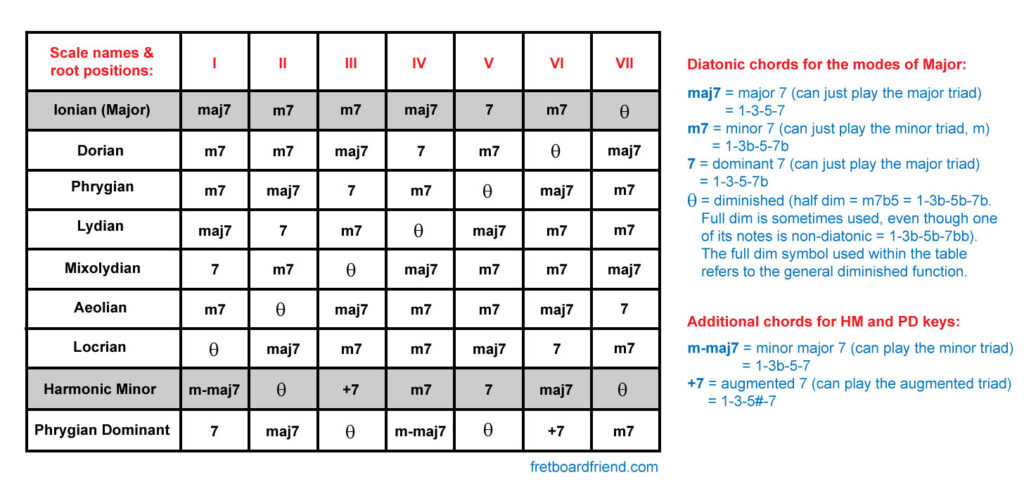

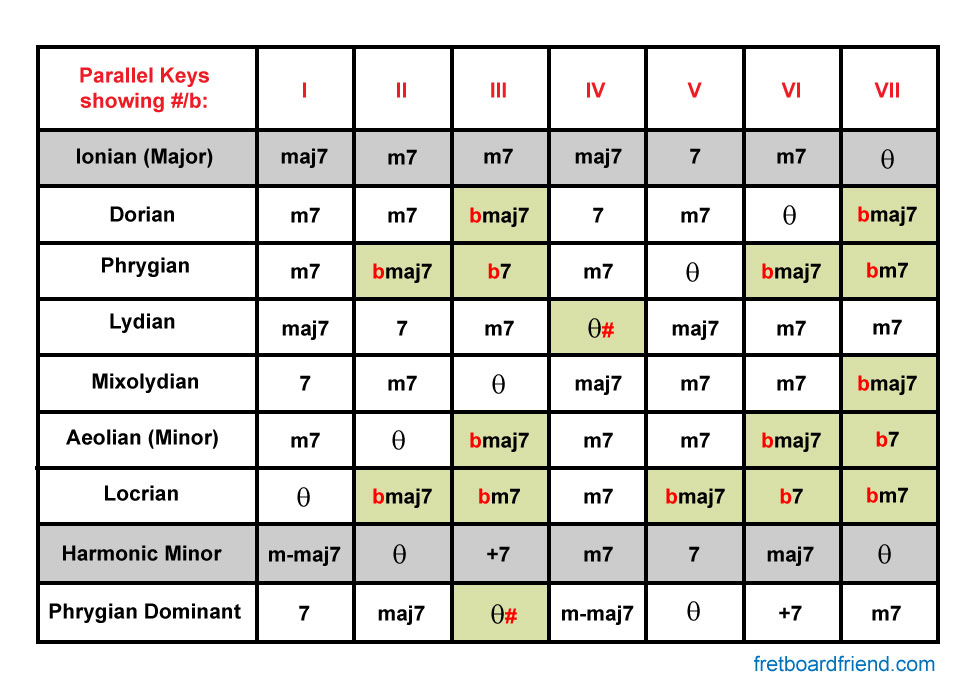

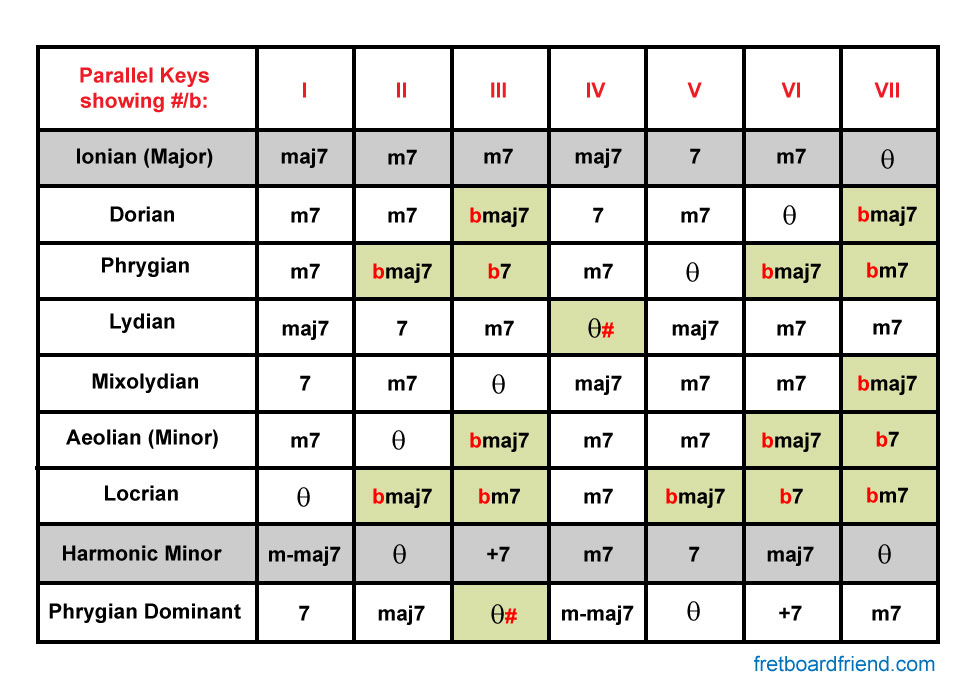

In the I-IV-V-I progression above, I knew that in the key of C Major, those chords would be C Major, F Major, G Dominant (or G Major triad), back to C Major. How did I know that there were no Minor chords in that progression? I just followed the diatonic-chord pattern rule, as per the table below. (Again, go watch Jake if you want to understand how that table was derived at.)

In the table below, I have written the extended (7) version of chords, meaning that there are 4 notes in each chord, but I could just as easily have written the table with their triad equivalents. That is,

- maj7 (major 7) = major triad.

- m7 (minor 7) = minor triad.

- 7 (dominant 7) = major triad.

It doesn’t really matter what the tonic note is for a particular key – whether it be in the key of C, D or E etc. Instead, it is the chord types in each root position that define the atmosphere of a song, because they define the scale-type. We can easily shift the tonic note up or down to suit a singer’s vocal range without dramatically changing the feel of a song (unless we shift the tonic by whole octaves).

In our example earlier, our progression is I-IV-V-I in the key of Ionian (Major). All chords are played as Major chords, though the fifth chord could also be played as a dominant chord if we wanted to extend it. What if we played the same progression (I-IV-V-I) in the key of Aeolian instead? Looking at the table below, you can see that all those chord types would change to Minor: Cm-Fm- Gm-Cm. The song will sound very similar, yet with a different mood. That’s the impact of changing the scale type (the mode) while the progression remains the same.

The Aeolian mode has the most ‘minor’ sound, meaning it is the most melancholic. The Ionian mode is the most upbeat. Now try the same progression in Dorian and Phrygian modes for comparison. In Dorian, positions IV and V are Major but I is Minor. In Phrygian, position IV and I are Minor but position V has a diminished chord.

It is generally said that Dorian, Phrygian and Aeolian are minor in flavour, while Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian are more major in flavour. Phrygian tends to be the most exotic. Mixolydian tends to be more jazzy, mixing both major and minor spacings. Locrian is often seen as the scale of ‘leftovers’, doing its own thing. Try playing the same progression in each mode (adapting chord types as necessary) to appreciate the different flavours of each mode.

Diatonic chord types for all Major modes and 2 Harmonic Minor modes:

The blues genre (and much popular rock) is built upon the IV-V-I chord progression. There is a feeling of needing to resolve from the V chord to the I chord. That ‘pulling back to resolve’ feeling is called cadence, and there are different kinds of cadence (such as the Andalusian cadence), as defined by the chord progression. YouTube is full of examples of popular chord progressions and specific types of cadences. Most (but not all) songs end on the first chord position (I).

Normal numerals (1, 2, 3 etc.) are used in chord formulas – not Roman numerals, which are used for chord progressions. The numbers in a chord formula always relate to the root note’s Major scale, regardless of what key the chord is being played in for that particular song. For example, imagine you are playing in the key of F Major. The root note of the fifth position (V) is C. The chord type for position V is dominant or a Major triad. The formula for a Major triad is 1-3-5. We do not take the 1-3-5 of F Major (the key of the song). We take 1-3-5 of C Major (the root note’s Major scale).

There are many chord formulas. The two most common ones are the Major triad (triad meaning just 3 notes) and Minor triad. The Major triad is 1-3-5 and the Minor is 1-3b-5, where the third note has been “flatted”. This third note (natural or flatted) is one of the most defining notes in any chord, changing its vibe from sunny to reflective.

Another defining note (in extended chords) is the 7th note. As chords get longer and longer (with more notes to play), choices have to be made about which notes to leave out because humans only have so many fingers to play with. Without going too far down the rabbit hole, one should note which notes in a chord formula are more defining than others (such as the 3rd and 7th positions being more defining than the 5th and the 1st positions). You might just choose to play those 2 notes out of an extended chord, which makes it confusing for anyone trying to analyse the song later, trying to decipher which chord those notes came from.

It’s not always the case that more notes (in a chord) sound better better than less. They just sound different. The more extended the chord, the more nuanced (less flexible) it is. Triads, on the other hand, are useful in that they can form the basis of multiple extended chords, and therefore a wider variety of chords can be played over the top of them. In fact, triads also allow different keys to be played on top of them at different times, so they can be used as ‘pivoting’ chords for modulation within a song.

From the diatonic chord table above, you can see which chord shapes are most common and therefore best to learn first (major, minor, 7th and half diminished, in that order). There are many more chord types though, such as augmented, but for most popular, Western songs, you can get by with learning the basics of these four chord types.

If you want to change things up, you could play each of these chords as an inversion (moving the bottom note to the top = first inversion, then again = second inversion). e.g. C Major chord is C-E-G. Its first inversion is E-G-C and its second inversion is G-C-E. This can get confusing when trying to analyse an existing song because you might think a chord is a version of an E or G chord when in fact it is an inversion of C. (i.e. The bottom note isn’t always the root note.) In the Extras section of this website, I touch on extended triads, which is when the root note isn’t even played but 3 notes from the extended chord are. If you’re confused, don’t worry, because I’ve jumped the gun a bit here. Suffice to say that I think it’s easier to build a song than to deconstruct one.

Aside from playing triads and their inversions, you could learn some extended versions (especially the 7th versions) of each chord, so Major7 instead of just the Major triad, and so on (Noting that a Dominant chord is always extended by nature, as its first 3 notes are a Major triad). Chords can be grouped by function (Major, Minor, Dominant, Diminished, Augmented, etc.) Any chord that has the same function is more or less interchangeable. For example, a Minor triad can be swapped for a Minor7, Minor 9, Minor13, and so on. Extended chords are built over multiple octaves so while it may look like the note from position 2 is being played when it is actually position 9 from the octave above.

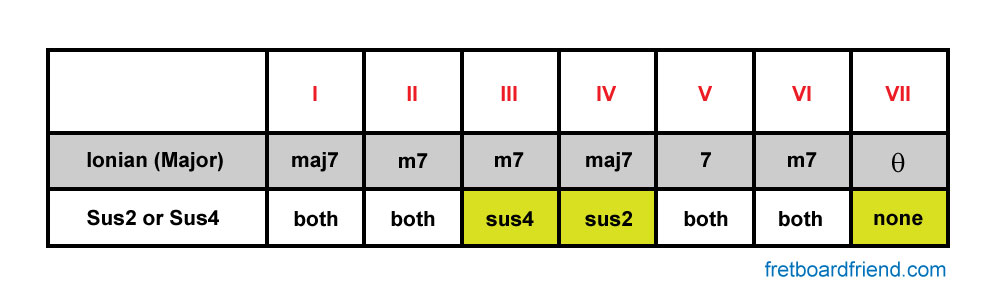

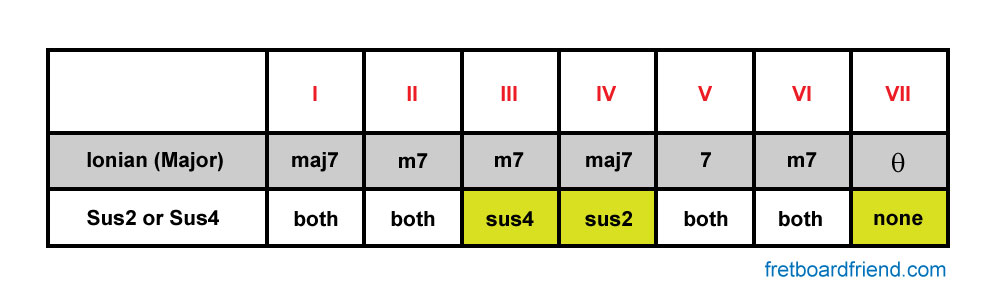

Lastly, there are some chords worth learning even though they are not in the diagnostic chord table above. That’s because they are more or less agnostic and thus easily substituted for other chords without changing the Major or Minor flavour of a song. These chords include power (“5”) chords (1-5-5) and suspended chords (sus2 = 1-2-5 and sus4 = 1-4-5) – including their inversions. Power chords and sus chords can be useful for breaking up long repetitive passages (instead of just sitting on a Major or Minor chord the whole time), or when you don’t want to define a song as being either major or minor (thereby allowing other instruments to swap between major and minor modes while playing lead over the top).

It’s important to note that sus2 and sus4 are not interchangeable in every diatonic chord position. Below is a chart showing where each one can be used within the Major mode. It is common to use Sus chords in position V of a progression (because V often wants to pull back to I and Sus chords contribute to that cadence). As a general rule, Sus2 sounds more interesting than Sus4 but Sus4 may have more cadence than Sus2. For more info on Suspended chords, check out this video and this.

Sus2 and Sus4 diatonic chord positions for Major:

Now that I’ve described diatonic chords (which will always sound in key), it’s time to have fun with non-diatonic chords and break some rules….

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Diatonic Chords

The last section described different scale types (pure, relative and parallel). This section describes different chord types in different positions within a scale/key. It also introduces the idea of chord progressions, chord formulas and chord-group functions. Indeed, things get extra dry below but you’ve got to know this stuff if you want to intentionally break rules later.

Every key has a set of diatonic chords for each root note (each position) within the scale. Diatonic means ‘within the key’ so nothing will sound out of tune. If everyone sticks to playing diatonic chords together, things can’t go too wrong. Just choose a key and stick to that set of chord types. Better yet, agree on a chord progression (the order that the chords are played in) and bingo, you have a song.

I won’t explain how diatonic chords are arrived at because your eyes may already be glazing over and I don’t want to lose you. Check out Jake Lizzio’s videos on YouTube if you want to know more. Otherwise just take it for granted that each key has a set of diatonic chord types for each position within the scale.

Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV etc.) show the position of each chord within the scale. Song progressions are written with these Roman numerals. For example, we could write a progression as I-IV-V-I. If we played that in the key of C Major (C Ionian), those chords would be C Major chord, then F Major chord, G Dominant chord (or G Major triad), back to C Major chord.

Note: If a chord is a Major chord, we don’t usually bother specifying that (as I did above). We would just write C-F-G7-C, where ‘7’ (not ‘maj7’ or ‘min7’ stands for ‘dominant 7’). If you’re not familiar with chord notations, check out this link. Note that some people distinguish between a Major and Minor chord in the chord progression by using capital Roman letters for Major (like I) and lower case Roman letters for Minor (i). I’m just going to use all caps and add the small ‘m’ to signify a Minor chord – so II = a Major chord but IIm = a Minor chord.

In the I-IV-V-I progression above, I knew that in the key of C Major, those chords would be C Major, F Major, G Dominant (or G Major triad), back to C Major. How did I know that there were no Minor chords in that progression? I just followed the diatonic-chord pattern rule, as per the table below. (Again, go watch Jake if you want to understand how that table was derived at.)

In the table below, I have written the extended (7) version of chords, meaning that there are 4 notes in each chord, but I could just as easily have written the table with their triad equivalents. That is,

- maj7 (major 7) = major triad.

- m7 (minor 7) = minor triad.

- 7 (dominant 7) = major triad.

It doesn’t really matter what the tonic note is for a particular key – whether it be in the key of C, D or E etc. Instead, it is the chord types in each root position that define the atmosphere of a song, because they define the scale-type. We can easily shift the tonic note up or down to suit a singer’s vocal range without dramatically changing the feel of a song (unless we shift the tonic by whole octaves).

In our example earlier, our progression is I-IV-V-I in the key of Ionian (Major). All chords are played as Major chords, though the fifth chord could also be played as a dominant chord if we wanted to extend it. What if we played the same progression (I-IV-V-I) in the key of Aeolian instead? Looking at the table below, you can see that all those chord types would change to Minor: Cm-Fm- Gm-Cm. The song will sound very similar, yet with a different mood. That’s the impact of changing the scale type (the mode) while the progression remains the same.

The Aeolian mode has the most ‘minor’ sound, meaning it is the most melancholic. The Ionian mode is the most upbeat. Now try the same progression in Dorian and Phrygian modes for comparison. In Dorian, positions IV and V are Major but I is Minor. In Phrygian, position IV and I are Minor but position V has a diminished chord.

It is generally said that Dorian, Phrygian and Aeolian are minor in flavour, while Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian are more major in flavour. Phrygian tends to be the most exotic. Mixolydian tends to be more jazzy, mixing both major and minor spacings. Locrian is often seen as the scale of ‘leftovers’, doing its own thing. Try playing the same progression in each mode (adapting chord types as necessary) to appreciate the different flavours of each mode.

Diatonic chord types for all Major modes and 2 Harmonic Minor modes:

The blues genre (and much popular rock) is built upon the IV-V-I chord progression. There is a feeling of needing to resolve from the V chord to the I chord. That ‘pulling back to resolve’ feeling is called cadence, and there are different kinds of cadence (such as the Andalusian cadence), as defined by the chord progression. YouTube is full of examples of popular chord progressions and specific types of cadences. Most (but not all) songs end on the first chord position (I).

Normal numerals (1, 2, 3 etc.) are used in chord formulas – not Roman numerals, which are used for chord progressions. The numbers in a chord formula always relate to the root note’s Major scale, regardless of what key the chord is being played in for that particular song. For example, imagine you are playing in the key of F Major. The root note of the fifth position (V) is C. The chord type for position V is dominant or a Major triad. The formula for a Major triad is 1-3-5. We do not take the 1-3-5 of F Major (the key of the song). We take 1-3-5 of C Major (the root note’s Major scale).

There are many chord formulas. The two most common ones are the Major triad (triad meaning just 3 notes) and Minor triad. The Major triad is 1-3-5 and the Minor is 1-3b-5, where the third note has been “flatted”. This third note (natural or flatted) is one of the most defining notes in any chord, changing its vibe from sunny to reflective.

Another defining note (in extended chords) is the 7th note. As chords get longer and longer (with more notes to play), choices have to be made about which notes to leave out because humans only have so many fingers to play with. Without going too far down the rabbit hole, one should note which notes in a chord formula are more defining than others (such as the 3rd and 7th positions being more defining than the 5th and the 1st positions). You might just choose to play those 2 notes out of an extended chord, which makes it confusing for anyone trying to analyse the song later, trying to decipher which chord those notes came from.

It’s not always the case that more notes (in a chord) sound better better than less. They just sound different. The more extended the chord, the more nuanced (less flexible) it is. Triads, on the other hand, are useful in that they can form the basis of multiple extended chords, and therefore a wider variety of chords can be played over the top of them. In fact, triads also allow different keys to be played on top of them at different times, so they can be used as ‘pivoting’ chords for modulation within a song.

From the diatonic chord table above, you can see which chord shapes are most common and therefore best to learn first (major, minor, 7th and half diminished, in that order). There are many more chord types though, such as augmented, but for most popular, Western songs, you can get by with learning the basics of these four chord types.

If you want to change things up, you could play each of these chords as an inversion (moving the bottom note to the top = first inversion, then again = second inversion). e.g. C Major chord is C-E-G. Its first inversion is E-G-C and its second inversion is G-C-E. This can get confusing when trying to analyse an existing song because you might think a chord is a version of an E or G chord when in fact it is an inversion of C. (i.e. The bottom note isn’t always the root note.) In the Extras section of this website, I touch on extended triads, which is when the root note isn’t even played but 3 notes from the extended chord are. If you’re confused, don’t worry, because I’ve jumped the gun a bit here. Suffice to say that I think it’s easier to build a song than to deconstruct one.

Aside from playing triads and their inversions, you could learn some extended versions (especially the 7th versions) of each chord, so Major7 instead of just the Major triad, and so on (Noting that a Dominant chord is always extended by nature, as its first 3 notes are a Major triad). Chords can be grouped by function (Major, Minor, Dominant, Diminished, Augmented, etc.) Any chord that has the same function is more or less interchangeable. For example, a Minor triad can be swapped for a Minor7, Minor 9, Minor13, and so on. Extended chords are built over multiple octaves so while it may look like the note from position 2 is being played when it is actually position 9 from the octave above.

Lastly, there are some chords worth learning even though they are not in the diagnostic chord table above. That’s because they are more or less agnostic and thus easily substituted for other chords without changing the Major or Minor flavour of a song. These chords include power (“5”) chords (1-5-5) and suspended chords (sus2 = 1-2-5 and sus4 = 1-4-5) – including their inversions. Power chords and sus chords can be useful for breaking up long repetitive passages (instead of just sitting on a Major or Minor chord the whole time), or when you don’t want to define a song as being either major or minor (thereby allowing other instruments to swap between major and minor modes while playing lead over the top).

It’s important to note that sus2 and sus4 are not interchangeable in every diatonic chord position. Below is a chart showing where each one can be used within the Major mode. It is common to use Sus chords in position V of a progression (because V often wants to pull back to I and Sus chords contribute to that cadence). As a general rule, Sus2 sounds more interesting than Sus4 but Sus4 may have more cadence than Sus2. For more info on Suspended chords, check out this video and this.

Sus2 and Sus4 diatonic chord positions for Major:

Now that I’ve described diatonic chords (which will always sound in key), it’s time to have fun with non-diatonic chords and break some rules….

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Non-Diatonic Chords

When you’re sticking to diatonic chords, everyone can play by the same rules and it’s happy days. That’s not to say you can ‘t break rules, but if there are other instruments playing harmonies, all instruments need to know what to expect or things could get ugly. If you’re playing solo, woohoo; you can experiment at will. Some approaches to non-diatonic chords are theoretical, while others are ‘just because’, stumbled across by chance. No doubt a theory exists for them, but at the end of the day, who cares if it sounds like it works anyway. This section gives ideas on how to branch out from diatonic chords via:

- Dominant chords

- Secondary Dominant chords

- modal mixture

- Diminished chords

- playing the changes.

So, the first thing one can experiment with, to introduce non-diatonic chords, is to turn every Major or Minor chord into a Dominant chord, regardless of its root position. Dom chords are cool, which is why jazz heads and blues players love them. Like its corresponding modal scale (Mixolydian), the Dom 7 chord contains both Major and Minor elements (a natural (not flatted) third with a flatted seventh). This gives it a bluesy vibe. Noodle in the Pentatonic Minor scale over a progression that only uses Dom chords and see how that sounds.

Even if you don’t go changing most chords to Dominants, the V position is frequently changed to a Dom if it isn’t already one, such as in Aeolian keys. That’s because a Dominant chord likes to resolve to a chord that is 5 steps below it. That means that a Dominant chord in the fifth position (V7) will resolve nicely to a I chord, regardless of whether that is a Major or Minor I chord. Being commonly used in both modes, the V7 is sometimes used to pivot between an Aeolian verse progression and an Ionian chorus progression within the one song. (Or between other modes, not just Aeolian and Ionian.)

Using the Circle of Fifths (basic version below), we can see which notes resolve to which because, well, the circle is made up of notes that are 5 steps apart. To the right of each note (clockwise) is a potential Dominant chord that wants to resolve to the note on its left. It just has a permanent ‘homing’ relationship to that note (in an anti-clockwise direction).

Basic circle of fifths showing how a V7 chord wants to resolve to either a major or minor chord on its left (anti-clockwise):

This underlies what is known as Secondary Dominant Chords, where one borrows ‘a mode of a mode‘. Using our previous IV-V-I example in the key of C Ionian, the V position is G Mixolydian. The fifth note in the scale of G Mixolydian is D. We could thus use D7 in place of the V chord (G7) in the key of C Ionian. i.e. Instead of playing F-G7-C, we could play F-D7-C. That would be written as IV-V/V-I, or more specifically, IV-V7/V7-I. A more complete resolution would be F-D7-G-G7-C (IV-V7/V7-V-V7-I). Even though the D7 chord (made up of D-F#-G-C) is not diatonic to the key of the song (because the C Ionian scale does not have an F# in it), the chord still works in this progression. Try it out to see what I mean.

Dominant chords don’t have to be in position V to resolve to position I. They can be used for any root position, like in the IV position (annotated as V7/IV) or the II position (annotated as V7/IIm). Here is another example: I-V7/IIm-IIm-V7-I. In the key of C Major, those chords would be: C-A7-Dm-G7-C. The Am chord will pull to the Dm, just as the G7 chord will pull to the C. That’s because A is 5 notes above D in the Dorian key and G is 5 notes above C in the Ionian key. The Am chord is not diatonic to the key of C Major, yet it works in that progression as a Secondary Dominant Chord.

You don’t have to take a ‘mode of mode’ approach to borrowed chords. You can just add ‘modal mixture‘, which is a fancy way of saying “try out different chord types with the same root note in any given position for the hell of it”. Try a Major, Minor, Dominant or Diminished chord for a start. As they are all chord types from the world of Major, if you are already in a mode of Major, you’ll be borrowing a chord from a parallel mode. Likewise, you can borrow between other pure scales (like Harmonic Minor modes).

Countless songs use borrowed chords. An example of modal mixture is ‘House of the Rising Sun’ by The Animals. It has these chords: Am-C-D-F (where only the first chord is a Minor chord, the rest are Major). Using the table below (as well as an earlier chart on key signatures), you can see that this key mostly fits A Aeolian and has a progression of Im-III-IV-VI. However, there is a glitch: the IV chord should be Minor, as per the chart below, yet in this progression it is Major. That means the IV chord is introducing a non-diatonic note (F# from the D Major chord) into the song. Why does it still sound ok? That D Major chord in the IV position has been borrowed from a D Major chord in the IV chord from a parallel key of A. The only parallel keys that have a Major chord in position IV are: Ionian, Dorian (noting that a Dominant and Major chord share the same triad), and Mixolydian. You don’t really need to define which of these it has been borrowed from but you might want to, in case you decide to borrow further from the same mode and/or improvise lead in that mode over the top while the borrowed chord is being played.

Parallel keys showing diatonic extended chord types and which notes are sharped or flatted relative to the pure parent scale:

Note: in the table above, Harmonic Minor and Phrygian Dominant are NOT parallel to the modes of Major above. I’ve just tacked them onto the bottom of the chart because I like them. Also note that the sharp (#) and flat (b) symbols are relative to the pure scale (Major or Harmonic Minor – to imply ‘sharped‘ or ‘flatted‘). They don’t necessarily mean that the note is itself called a sharp or a flat. If you already know all your Major scales (key signatures), this table will give you a quick way of deducing the key of a song if you can hear what the tonic note is.

Jake Lizzio can illustrate modal mixture much better than I ever could with my printed words, so check out his video below.

When going about modal mixture, it helps to consider the temperament of the different chord types. To my ear, it sounds like:

- Major is sunny

- Minor is overcast

- Dominant is sunny with just a chance of rain

- Diminished is dark with storm clouds overhead.

Now I’m going to hang on the topic of Diminished chords for a bit. Although they have a bit of an odd sound, Diminished chords can be theoretically quite useful, especially when breaking diatonic rules. For one thing, a full diminished chord is always diatonic to eight keys at the same time, which is useful if pivoting between keys. (I won’t unpack that here – watch a video link below if that interests you.)

The main thing to know about Dim chords is that, like Dom chords, they like to resolve to another chord. In particular, they like to resolve to a Minor or Major chord with the same root note (which means they can be used to pivot between a Major and a Minor key). In contrast, a Dom chord wants to resolve to a Major or Minor chord that is 5 steps below it.

Here is an example of a non-diatonic Dim chord in a progression: Am-Ao-Am-Ao-G7-G7 (where Ao = the diminished A chord). The structure is VIm-VIo-VIm-VIo-V7-V7 in the key of C Major. Although the VIo chord is not diatonic, the progression works, with Ao being drawn to Am because the Dim chord wants that resolution.

Up until now I’ve been pretty lazy by using ‘o’ to represent a general diminished chord function – but there is a difference between half diminished and full diminished chords. The full dim has one note that isn’t diatonic to the modes of Major – so you should opt for the half dim in most circumstances. (The full dim is diatonic to the modes of Harmonic Minor instead.) From here on, I will distinguish between the full dim and half dim by using the mouthy name for the half dim = ‘m7b5’ (minor-7 flat-5).

It should also be noted that aside from wanting to resolve to a Minor or Major chord with the same root, a diatonic diminished chord (m7b5 in the world of Major, or full diminished in the world of Harmonic Minor) will also have cadence to the key’s tonic chord (position I). That cadence will not be as strong as the pull from a Dominant chord to I.

You can get a feel for these different cadences (Dom vs Dim) by playing the following chords…. In Aeolian: IIo-Im, then V7-Im, then IIo-V7-Im. In the key of A Aeolian, those chords would be Am (I), Bo (IIo) and E7 (V7). Then change to the Ionian mode by playing VIIo-I, V7-I, then VIIo-V7-I. In the key of A Ionian, those chords would be A (I), Go (VIIo) and E7 (V7).

If you want to know more about Diminished chords, see the links below from Jake’s Signals Music Studio:

- Deconstructing Diminished Chords

- Five Ways to use Diminished Chords

- Dim 7 Chord – Portal to 8 Tonalities

- Does the Diminished VIIo Chord even exist?

The last approach you might consider when introducing non-diatonic chords is to ‘play the changes‘. This approach is popular with jazz-heads. It applies more to the lead melody than to the underlying chord progression. Basically, you change the key of the lead every time a chord changes within the progression. The lead keys are not related to each other but chords beneath them are connected by one over-arching key.

That sounds more confusing than it needs to so I’ll use an example with this chord progression: Dm-G-Am-F-Bm7b5-E-Am-A7. Looking at the key signature (i.e. presence or absence of sharps and flats), this key probably belongs to a relative mode of C Ionian. Looking at the chord types, the best fit is with C Ionian itself but there are exceptions: E is Major (not Minor, so it is borrowed) and an A7 has been tacked onto the end because that allows the progression to loop. (A is 5 notes above D in the Circle of Fifths so A7 will draw us back to the beginning of this progression.)

Somewhat confusingly, although it looks like C Ionian (C Major) is the key, the I chord (C Major) does not appear and nor does it sound like a resolving tonic chord. Try it for yourself. Even after dropping a chord or two from the end of the progression, C Major chord sounds odd, doesn’t it? I can imagine starting a second passage with it but I can’t see how to nicely work it into this progression (and rather chuffed that I came up with a great example here).

To test whether or not the key really is in C Ionian, we can noodle over the top in the C Ionian scale. That will tell us pretty quickly whether or not it fits and hooray, it does. (Be aware while noodling that the non-diatonic chords of E Major and A7 will not want certain C Ionian notes played on top of them – namely G (not over E Major) and C (not over A7). You can look up the notes of the E Major chord and A7 chord to appreciate why these chords would clash over G and C respectively.)

Now, while we were noodling about, we remained in one scale (C Ionian) for the lead. That’s where a jazz muso might instead play the changes. They would noodle in a scale that suits just the chord that is being played beneath it. They would play a D minor scale (such as D Dorian or D Aeolian) while playing over the Dm chord. And whenever the G chord was played, they might noodle in any key that has G Major or G7 as its tonic chord. And so on. No doubt they can get fancier than that – throwing in some inverted extended triads of modes–of-modes just to mess with fellow jazzheads! The interesting things is, even though we decided that the overall key was C Ionian, if you play the changes, the lead will never noodle over the top in that scale.

That’s why jazz music can sound so complex; it layers keys within keys (plus it uses other scales, like Bepop and Melodic Minor, which are less familiar to us.) Who am I kidding? I don’t know jazz! These are all just my assumptions. If you want to hear some noodling that sounds to me like jazz, check out the video below. I have no idea what scales they’re using around the 2 minute mark but I don’t think they’re sticking to the overall key of the song. By the way, the original song (“Sunny” by Bobby Hebb) is interesting in its own right because it modulates every time the verse and chorus repeat, moving up a semitone each time – but I don’t think that’s happening in the video below. They’re just changing keys within the lead on occasion, not within the underlying progression of chords.

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Non-Diatonic Chords

When you’re sticking to diatonic chords, everyone can play by the same rules and it’s happy days. That’s not to say you can ‘t break rules, but if there are other instruments playing harmonies, all instruments need to know what to expect or things could get ugly. If you’re playing solo, woohoo; you can experiment at will. Some approaches to non-diatonic chords are theoretical, while others are ‘just because’, stumbled across by chance. No doubt a theory exists for them, but at the end of the day, who cares if it sounds like it works anyway. This section gives ideas on how to branch out from diatonic chords via:

- Dominant chords

- Secondary Dominant chords

- modal mixture

- Diminished chords

- playing the changes.

So, the first thing one can experiment with, to introduce non-diatonic chords, is to turn every Major or Minor chord into a Dominant chord, regardless of its root position. Dom chords are cool, which is why jazz heads and blues players love them. Like its corresponding modal scale (Mixolydian), the Dom 7 chord contains both Major and Minor elements (a natural (not flatted) third with a flatted seventh). This gives it a bluesy vibe. Noodle in the Pentatonic Minor scale over a progression that only uses Dom chords and see how that sounds.

Even if you don’t go changing most chords to Dominants, the V position is frequently changed to a Dom if it isn’t already one, such as in Aeolian keys. That’s because a Dominant chord likes to resolve to a chord that is 5 steps below it. That means that a Dominant chord in the fifth position (V7) will resolve nicely to a I chord, regardless of whether that is a Major or Minor I chord. Being commonly used in both modes, the V7 is sometimes used to pivot between an Aeolian verse progression and an Ionian chorus progression within the one song. (Or between other modes, not just Aeolian and Ionian.)

Using the Circle of Fifths (basic version below), we can see which notes resolve to which because, well, the circle is made up of notes that are 5 steps apart. To the right of each note (clockwise) is a potential Dominant chord that wants to resolve to the note on its left. It just has a permanent ‘homing’ relationship to that note (in an anti-clockwise direction).

Basic circle of fifths showing how a V7 chord wants to resolve to either a major or minor chord on its left (anti-clockwise):

This underlies what is known as Secondary Dominant Chords, where one borrows ‘a mode of a mode‘. Using our previous IV-V-I example in the key of C Ionian, the V position is G Mixolydian. The fifth note in the scale of G Mixolydian is D. We could thus use D7 in place of the V chord (G7) in the key of C Ionian. i.e. Instead of playing F-G7-C, we could play F-D7-C. That would be written as IV-V/V-I, or more specifically, IV-V7/V7-I. A more complete resolution would be F-D7-G-G7-C (IV-V7/V7-V-V7-I). Even though the D7 chord (made up of D-F#-G-C) is not diatonic to the key of the song (because the C Ionian scale does not have an F# in it), the chord still works in this progression. Try it out to see what I mean.

Dominant chords don’t have to be in position V to resolve to position I. They can be used for any root position, like in the IV position (annotated as V7/IV) or the II position (annotated as V7/IIm). Here is another example: I-V7/IIm-IIm-V7-I. In the key of C Major, those chords would be: C-A7-Dm-G7-C. The Am chord will pull to the Dm, just as the G7 chord will pull to the C. That’s because A is 5 notes above D in the Dorian key and G is 5 notes above C in the Ionian key. The Am chord is not diatonic to the key of C Major, yet it works in that progression as a Secondary Dominant Chord.

You don’t have to take a ‘mode of mode’ approach to borrowed chords. You can just add ‘modal mixture‘, which is a fancy way of saying “try out different chord types with the same root note in any given position for the hell of it”. Try a Major, Minor, Dominant or Diminished chord for a start. As they are all chord types from the world of Major, if you are already in a mode of Major, you’ll be borrowing a chord from a parallel mode. Likewise, you can borrow between other pure scales (like Harmonic Minor modes).

Countless songs use borrowed chords. An example of modal mixture is ‘House of the Rising Sun’ by The Animals. It has these chords: Am-C-D-F (where only the first chord is a Minor chord, the rest are Major). Using the table below (as well as an earlier chart on key signatures), you can see that this key mostly fits A Aeolian and has a progression of Im-III-IV-VI. However, there is a glitch: the IV chord should be Minor, as per the chart below, yet in this progression it is Major. That means the IV chord is introducing a non-diatonic note (F# from the D Major chord) into the song. Why does it still sound ok? That D Major chord in the IV position has been borrowed from a D Major chord in the IV chord from a parallel key of A. The only parallel keys that have a Major chord in position IV are: Ionian, Dorian (noting that a Dominant and Major chord share the same triad), and Mixolydian. You don’t really need to define which of these it has been borrowed from but you might want to, in case you decide to borrow further from the same mode and/or improvise lead in that mode over the top while the borrowed chord is being played.

Parallel keys showing diatonic extended chord types and which notes are sharped or flatted relative to the pure parent scale:

Note: in the table above, Harmonic Minor and Phrygian Dominant are NOT parallel to the modes of Major above. I’ve just tacked them onto the bottom of the chart because I like them. Also note that the sharp (#) and flat (b) symbols are relative to the pure scale (Major or Harmonic Minor – to imply ‘sharped‘ or ‘flatted‘). They don’t necessarily mean that the note is itself called a sharp or a flat. If you already know all your Major scales (key signatures), this table will give you a quick way of deducing the key of a song if you can hear what the tonic note is.

Jake Lizzio can illustrate modal mixture much better than I ever could with my printed words, so check out his video below.

When going about modal mixture, it helps to consider the temperament of the different chord types. To my ear, it sounds like:

- Major is sunny

- Minor is overcast

- Dominant is sunny with just a chance of rain

- Diminished is dark with storm clouds overhead.

Now I’m going to hang on the topic of Diminished chords for a bit. Although they have a bit of an odd sound, Diminished chords can be theoretically quite useful, especially when breaking diatonic rules. For one thing, a full diminished chord is always diatonic to eight keys at the same time, which is useful if pivoting between keys. (I won’t unpack that here – watch a video link below if that interests you.)

The main thing to know about Dim chords is that, like Dom chords, they like to resolve to another chord. In particular, they like to resolve to a Minor or Major chord with the same root note (which means they can be used to pivot between a Major and a Minor key). In contrast, a Dom chord wants to resolve to a Major or Minor chord that is 5 steps below it.

Here is an example of a non-diatonic Dim chord in a progression: Am-Ao-Am-Ao-G7-G7 (where Ao = the diminished A chord). The structure is VIm-VIo-VIm-VIo-V7-V7 in the key of C Major. Although the VIo chord is not diatonic, the progression works, with Ao being drawn to Am because the Dim chord wants that resolution.

Up until now I’ve been pretty lazy by using ‘o’ to represent a general diminished chord function – but there is a difference between half diminished and full diminished chords. The full dim has one note that isn’t diatonic to the modes of Major – so you should opt for the half dim in most circumstances. (The full dim is diatonic to the modes of Harmonic Minor instead.) From here on, I will distinguish between the full dim and half dim by using the mouthy name for the half dim = ‘m7b5’ (minor-7 flat-5).

It should also be noted that aside from wanting to resolve to a Minor or Major chord with the same root, a diatonic diminished chord (m7b5 in the world of Major, or full diminished in the world of Harmonic Minor) will also have cadence to the key’s tonic chord (position I). That cadence will not be as strong as the pull from a Dominant chord to I.

You can get a feel for these different cadences (Dom vs Dim) by playing the following chords…. In Aeolian: IIo-Im, then V7-Im, then IIo-V7-Im. In the key of A Aeolian, those chords would be Am (I), Bo (IIo) and E7 (V7). Then change to the Ionian mode by playing VIIo-I, V7-I, then VIIo-V7-I. In the key of A Ionian, those chords would be A (I), Go (VIIo) and E7 (V7).

If you want to know more about Diminished chords, see the links below from Jake’s Signals Music Studio:

- Deconstructing Diminished Chords

- Five Ways to use Diminished Chords

- Dim 7 Chord – Portal to 8 Tonalities

- Does the Diminished VIIo Chord even exist?

The last approach you might consider when introducing non-diatonic chords is to ‘play the changes‘. This approach is popular with jazz-heads. It applies more to the lead melody than to the underlying chord progression. Basically, you change the key of the lead every time a chord changes within the progression. The lead keys are not related to each other but chords beneath them are connected by one over-arching key.

That sounds more confusing than it needs to so I’ll use an example with this chord progression: Dm-G-Am-F-Bm7b5-E-Am-A7. Looking at the key signature (i.e. presence or absence of sharps and flats), this key probably belongs to a relative mode of C Ionian. Looking at the chord types, the best fit is with C Ionian itself but there are exceptions: E is Major (not Minor, so it is borrowed) and an A7 has been tacked onto the end because that allows the progression to loop. (A is 5 notes above D in the Circle of Fifths so A7 will draw us back to the beginning of this progression.)

Somewhat confusingly, although it looks like C Ionian (C Major) is the key, the I chord (C Major) does not appear and nor does it sound like a resolving tonic chord. Try it for yourself. Even after dropping a chord or two from the end of the progression, C Major chord sounds odd, doesn’t it? I can imagine starting a second passage with it but I can’t see how to nicely work it into this progression (and rather chuffed that I came up with a great example here).

To test whether or not the key really is in C Ionian, we can noodle over the top in the C Ionian scale. That will tell us pretty quickly whether or not it fits and hooray, it does. (Be aware while noodling that the non-diatonic chords of E Major and A7 will not want certain C Ionian notes played on top of them – namely G (not over E Major) and C (not over A7). You can look up the notes of the E Major chord and A7 chord to appreciate why these chords would clash over G and C respectively.)

Now, while we were noodling about, we remained in one scale (C Ionian) for the lead. That’s where a jazz muso might instead play the changes. They would noodle in a scale that suits just the chord that is being played beneath it. They would play a D minor scale (such as D Dorian or D Aeolian) while playing over the Dm chord. And whenever the G chord was played, they might noodle in any key that has G Major or G7 as its tonic chord. And so on. No doubt they can get fancier than that – throwing in some inverted extended triads of modes–of-modes just to mess with fellow jazzheads! The interesting things is, even though we decided that the overall key was C Ionian, if you play the changes, the lead will never noodle over the top in that scale.

That’s why jazz music can sound so complex; it layers keys within keys (plus it uses other scales, like Bepop and Melodic Minor, which are less familiar to us.) Who am I kidding? I don’t know jazz! These are all just my assumptions. If you want to hear some noodling that sounds to me like jazz, check out the video below. I have no idea what scales they’re using around the 2 minute mark but I don’t think they’re sticking to the overall key of the song. By the way, the original song (“Sunny” by Bobby Hebb) is interesting in its own right because it modulates every time the verse and chorus repeat, moving up a semitone each time – but I don’t think that’s happening in the video below. They’re just changing keys within the lead on occasion, not within the underlying progression of chords.

Copyright Reading Insights Pty Ltd

Songwriting Ideas

- switch keys between verse and chorus

- pivot to new sections and keys via diminished chords

- convert chords from triads to extended (espeically doms) or vice versa

- invert chords

- add secondary dominant chords

- add suspended chords

- drone / pedal

- lament bass (walk a section down in semitones or tones, then build chords off that)

- counterpoint (delay the start of the melody as an overlay, like you would in a round robin – or invert the melody, as overlay, AKA contrapuntal).

Songwriting Ideas

- switch keys between verse and chorus

- pivot to new sections and keys via diminished chords

- convert chords from triads to extended (espeically doms) or vice versa

- invert chords

- add secondary dominant chords

- add suspended chords

- drone / pedal

- lament bass (walk a section down in semitones or tones, then build chords off that)

- counterpoint (delay the start of the melody as an overlay, like you would in a round robin – or invert the melody, as overlay, AKA contrapuntal).

Extras

5 day Blues Course by Signals Music Studio (free).

The Phrygian Dominant key by Signals Music Studio:

Andalusian Cadence by Signals Music Studio:

Five steps to jamming solo by Corey Huevel:

Triads are the answer by Active Melody:

After watching the last video, you might find this info relevant:

- To form a Major 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Major key. (For Cmaj7, play Em over C.)

- To form a Minor 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Aeolian key. (For Am7, play C over A.)

- To form a Dominant 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Mixolydian key. (For G7, play Bm7b5 over G.)

- To form a Major 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Major key. (For Cmaj9, play G (triad) over C.)

- To form a Minor 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Aeolian key. (For Am7, play Em over A).

- To form a Dominant 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Mixolydian key. (For G9, play Dm over G).

Extras

5 day Blues Course by Signals Music Studio (free).

The Phrygian Dominant key by Signals Music Studio:

Andalusian Cadence by Signals Music Studio:

Five steps to jamming solo by Corey Huevel:

Triads are the answer by Active Melody:

After watching the last video, you might find this info relevant:

- To form a Major 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Major key. (For Cmaj7, play Em over C.)

- To form a Minor 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Aeolian key. (For Am7, play C over A.)

- To form a Dominant 7 triad, play diatonic chord III over target note I from the Mixolydian key. (For G7, play Bm7b5 over G.)

- To form a Major 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Major key. (For Cmaj9, play G (triad) over C.)

- To form a Minor 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Aeolian key. (For Am7, play Em over A).

- To form a Dominant 9 triad, play diatonic chord V over target note I in the Mixolydian key. (For G9, play Dm over G).